MYTHOLOGIES OF THE ARAPAHO/CHEYENNE TRIBES

Northern Cheyenne Tribe

600 Cheyenne Ave

Littlewolf Capital Building

P.O. Box 128

Lame Deer, Montana 59043

Main Phone: (406) 477-6284

Fax: (406) 477-6210

The Arapaho tribe of Native Americans historically lived on the eastern plains of Colorado and Wyoming, although they originated in the Great Lakes region as relatively peaceful farmers. The Arapaho language is an Algonquian language related to the language of the Gros Ventre people, who are seen as an early offshoot of the Arapaho. After adopting the Plains culture, Arapaho bands separated into two tribes: the Northern Arapaho and Southern Arapaho. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Sioux, fighting with them in the Indian Wars. The expansion of white interests led to the end of their way of life. With their buffalo herds gone and defeated in battle, they were moved to Indian reservations. The Northern Arapaho Nation continue to live with the Eastern Shoshone on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. The Southern Arapaho Tribe lives with the Southern Cheyenne in Oklahoma. Together their members are enrolled as a federally recognized tribe, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

- Splinter Foot Girl

- The Lame Warrior

- The Star Husband

- The Sun Dance Wheel

- George Quiver Visits the Doctor

- The two bullets

- Jumping the Canyon

- The owl man

- Old Couple and the Ghost

- Fooling the Ghost

- The Girl Who Climbed to the Sky

- The Girl Enticed to the Sky

- How Medicine Man Resurrected Buffalo

- The Lame Warrior and the Skeleton

- Nihancan and the Dwarf’s Arrow

- Strong bear and the Wagon

- Strong bear Shakes Hands

- Strong bear and the Boxer

- Strong bear and the Ghost

- The Two Sons

- The Crow Chief

- Blood clot boy

- Splitting of the Tribes

- The Good Garden

- The Satisfied Bear

- The King of Birds

- Killing Racer

- Where Nooke’ei Beh’ei Unravelled Himself

- Nooke’ei Beh’ei has a Narrow Escape

- The Dwarf

- The Man who Ran Horses

Five Prominent Figures in Cheyenne Mythology

Maheo is also known as the Great Spirit or the Master of Life among the Cheyenne. Maheo is the equivalent of God or creator. Maheo is very rarely personified due to the fact that Maheo has no human form. Like the Creator in most creation stories, Maheo created the world out of the void.

This is the name of the powerful and respected Cheyenne thunder spirit. Nonoma has been described and portrayed in various forms, from being a large bird to being an abstract entity. Nonoma, being the enemy of water monsters, is also closely related to the summer season.

Every mythology has a quintessential trickster character. A trickster is a character in folklore that is knowledgeable but sly and does not conform to rules. A trickster likes to get in trouble and enjoy getting other characters in troublesome situations as well. In Cheyenne mythology, Veeho is a trickster associated with spiders.

Ahke or Axxea is a lake monster that devours humans. Most depictions of Ahke show the monster as an underwater serpent while other representations feature Ahke as a four-legged monster.

The Cheyenne consider Sweet Medicine as a legendary prophet of their tribe. Among the things that made him legendary was his foresight regarding the white men setting food on their lands.

NIANTHAW

This spider spirit comes from the Arapaho tribe. The name can be pronounced Ni-AN-thaw or Ni-AN-saw. Sometimes, this spirit can be a positive transformer, helping humans, but often the spider Nianthaw enjoys tricking humans to their detriment. The name might work for a horse that likes to occasionally try to dump its rider on the ground or step on their foot but is generally a pretty good-natured horse.

The Northern Arapaho were living along the Platte River years ago. At that time the different tribes, such as the Shoshoni, Crow, Sioux,—the most friendly ones, used to come around with a certain amount of skins and furs, to trade with the tribe. As the Crow Indians were good marksmen, they had quite a supply of elk skin when they came to the camp-circle, which was on the south side of the Platte River. Quite a good many Arapaho caught their big horses and packed their goods to trade with the Crow Indians. Our horses were out far in the prairie, and my boys caught the tamest, which were very small. So I took some beads and a few other articles and got on the pony. The Platte River was high that year, and was very dangerous, being swift. Twice I was out of elk skin, which I needed for various things. I aimed to get some that day. The other Arapaho had reached the other shore all right, and it came my turn to cross. I was not afraid at all, putting my faith in the pony; so I rode in the river.

Lodge-Boy And Thrown-Away’s Father

- The Trickster Kills The Children

- Nihoo3oo and the Fox

- Nihoo3oo and the Ducks

- Nihoo3oo and the Entrails

- Nihoo3oo and the Butt

- Nihoo3oo and the Rock

Five nations from south to north

- Nanwacinaha’ana, Nawathi’neha (“Toward the South People”) or Nanwuine’nan / Noowo3iineheeno’ (“Southern People”). Their now-extinct language dialect – Nawathinehena – was the most divergent from the other Arapaho tribes.

- Hánahawuuena, Hananaxawuune’nan or Aanû’nhawa (“Rock Men” or “Rock People”), occupying territory adjacent to, but further north of the Nanwacinaha’ana, spoke the now-extinct Ha’anahawunena dialect.

- Hinono’eino or Hinanae’inan (“Arapaho proper”) spoke the Arapaho language (Heenetiit).

- Beesowuunenno’, Baasanwuune’nan or Bäsawunena (“Big Lodge People” or “Brush-Hut/Shelter People”) resided further north of the Hinono’eino. Their war parties used temporary brush shelters similar to the dome-shaped shade or Sweat lodge of the Great Lakes Algonquian peoples. They are said to have migrated from their former territory near the Lakes more recently than the other Arapaho tribes. (Note: many people say their name means “Great Lakes People” or “Big Water People”.) They spoke the now-extinct Besawunena (Beesoowuuyeitiit – “Big Lodge/Great Lakes language”) dialect.

- Haa’ninin, A’aninin or A’ani (“White Clay People” or “Lime People”), the northernmost tribal group; they retained a distinct ethnicity and were known to the French as the historic Gros Ventre. In Blackfoot they were called Atsina (Atsíína – “like a Cree“, i.e. “enemy”, or Piik-siik-sii-naa – “snakes”, i.e. “enemies”). After they separated, the other Arapaho peoples, who considered them inferior, called them Hitúnĕna or Hittiuenina (“Begging Men”, “Beggars”, or more exactly “Spongers”). They speak the nearly extinct Gros Ventre (Ananin, Ahahnelin) language dialect (called by the Arapaho Hitouuyeitiit – “Begging Men Language”), there is evidence that the southern Haa’ninin tribal group, the Staetan band, together with bands of the later political division of the Northern Arapaho, spoke the Besawunena dialect.

Arapaho – Great Buffalo Hunters of the Plains

The Arapaho Indians have lived on the plains of Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Kansas since the 17th Century. Before that, they had roots in Minnesota before European expansion forced them westward. They were a sedentary, agricultural people living in permanent villages in the eastern woodlands. However, that changed when they moved west, and the tribe became a nomadic people following the great buffalo herds. The Arapaho refer to themselves as ‘Inuna-Ina’ which translates to “our people.” Their language is of Algonquin heritage, as is that of their close neighbors, the Cheyenne. When they began to drift west, the Arapaho soon became close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and were later loosely aligned with the Sioux.

CHEYENNE-ARAPAHO MYTHOLOGY

The Cheyenne-Arapaho mythology brings together the following Native American peoples: Arapahos, Cow People, Cheyennes, Atsinas, Gros Ventres, Blackfoot Confederation. The Arapahos (also called Arapahoes Where Cow People in French) are an Amerindian tribe. During the time of European colonization they lived in the plains of eastern Colorado and Wyoming.

This sacred ritual occurs during the summer time(August & July) and is held on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. The Sun dance normally is around the time of the summer solstice. This used to sometimes be held in Oklahoma, but it is not anymore. During the ritual, people dance, sing, have visions, fast, play the drums, and in some cases- self torture. It is a symbolic meaning of the ceremony as a celebration of the generative power of the sun. After four days, the Sun Dance ends.

Eagle

The eagle in the Sun Dance is the “messenger” of communication between man and spirit. The eagle’s feathers can cure illnesses. Throughout the Sun Dance a medicine man may use his eagle feather for healing, first touching the feather to the sun-pole then to the patient, transferring the energy from the pole to the ill people.

Buffalo

The buffalo, however, makes up the main theme of the Sun Dance. In various stories it was the buffalo that began the ritual. Buffalo songs, dances, and feast commonly accompany the Sun Dance.The buffalo also has a great role in the visions. The buffalo may knock down a dancer, or the dancer may challenge the buffalo by charging at it. Passing out for too long means one was too afraid to face the buffalo. One must show courage and stand up to the buffalo before the buffalo finds him worthy to give him what he desires. When the Crow notices he is seeing through the buffalo’s eyes, he has become one with the buffalo.

A ceremonial religious dance connected with the messianic religion, which originated among the Paviotso in Nevada about 1888. It spread rapidly among other tribes-from the Missouri river to or beyond the Rockies. The prophet of the religion was a young Paiute Indian, who was almost 35 years old at the time. Among his own people, however, he was known as Wocoka, and commonly called by the whites Jack Wilson. In 1888 Wovoka, who was a medicine-man, caught a dangerous fever. While he was ill, an eclipse spread excitement among the Indians, with the result that Wovoka became delirious and imagined that he had been taken into the spirit world. There he received a direct revelation from the God of the Indians that basically said the revelation was to the effect that a new dispensation was close at hand-by which the Indians would be restored to their inheritance and reunited with their departed friends. They also must prepare for the event by practicing the songs and dance ceremonies which the prophet gave them. Within a very short time the dance became commonly known as the Spirit or Ghost.

TEIHIIHAN: THE LITTLE CANNIBALS OF THE PLAINS

The word “Teihiihan” was derived from the Arapaho word meaning “strong.” They were also termed as “Hecesiiteihii” which meant little people. The Teihiihan were child-sized Dwarfs, who were insanely strong, aggressive, bloodthirsty cannibals who attacked in large groups. Their violent nature was because they believed that dying in battle was the only way to reach the afterlife. Various folklores have stated that they used to possess dangerous magical powers or witchcraft and could go invisible while preying on the tribes. According to the myths, these cannibals lived in the Great Plains of America, between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. There are mentions of the Teihiihan in the legends of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Omaha, Kanza, Shoshone, Comanche, and Ponca tribes.It was also stated that the entire race of the Teihiihan was killed in a war by the Arapaho tribe and their allies.

TSE-TSEHESE-STAESTSE

(CHEYENNE

LITERATURE)

http://www.indigenouspeople.net/cheyenne.htm

RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND CUSTOMS OF THE CHEYENNE TRIBE

These religious people held Ma’heo’o as the creator of both physical and spiritual life and the four sacred arrows as the most revered object. Among the events and accomplishments that these tribes celebrated through rituals, smoking of the ceremonial pipe, Calumet, was a custom that was greatly valued. As this pipe was used for sealing a peace treaty, it was referred to as a “Peace Pipe.” Traditional ceremonies like the Sun Dance, Animal Dance and Arrow Renewal are still recognized as sacred and private today.

The Cheyenne creation story recounts the formation of the world by the tribe’s Divine Being, Ma’heo’. Some of their myths and legends narrate the exploits of certain figures such as the spirit of thunder or “Nonoma,” or the spider trickster, “Wihio.”

Drawing by Bear’s Heart (Cheyenne)

“A nation is not conquered

Until the hearts of its women are on the ground.

Then it is finished,

No matter how brave its warriors

Or how strong their weapons.”

Cheyenne proverb

Hanaya, Netonetomohta

“He, our Father, He has shown His mercy unto me.

In peace I walk the straight road”

Morning Song

HISTORY

The earliest known written historical record of the Cheyenne comes from the mid-17th century, when a group of Cheyenne visited the French Fort Crevecoeur, near present-day Peoria, Illinois. The Cheyenne at this time lived between the Mississippi River and Mille Lacs Lake. Their economy was based on the collection of wild rice and hunting, especially of bison, which lived in the prairies 70–80 miles west of the Cheyenne villages.

According to tribal history, during the 17th century, the Cheyenne had been driven by the Assiniboine (Hóheeheo’o – “wrapped ones or swaddled”, adaptive from the Lakota/Dakota word Hóhe, meaning “rebels”) from the Great Lakes region to present-day Minnesota and North Dakota, where they established villages. The most prominent of the ancient Cheyenne villages is Biesterfeldt Village, in eastern North Dakota along the Sheyenne River. The tribal history also relates that they first reached the Missouri River in 1676. A more recent analysis of early records posits that at least some of the Cheyenne remained in the Mille Lac region of Minnesota until about 1765, when the Ojibwe defeated the Lakota with firearms — pushing the Cheyenne, in turn, to the Minnesota River, where they were reported in 1766.

On the Missouri River, the Cheyenne came into contact with the neighboring Mandan, Hidatsa (Tsé-heše’émâheónese, “people who have soil houses“), and Arikara people (Ónoneo’o), and they adopted many of their cultural characteristics. They were first of the later Plains tribes into the Black Hills and Powder River Country. About 1730, they introduced the horse to Lakota bands (Ho’óhomo’eo’o – “the invited ones (to Cheyenne lands i.e. the Black Hills)”). Conflict with migrating Lakota and Ojibwe people forced the Cheyenne further west, and they, in turn, pushed the Kiowa to the south.

By 1776, the Lakota had overwhelmed the Cheyenne and taken over much of their territory near the Black Hills. In 1804, Lewis and Clark visited a surviving Cheyenne village in what is now North Dakota. Such European explorers learned many different names for the Cheyenne and did not realize how the different sections were forming a unified tribe.

The Cheyenne Nation is descended from two related tribes, the Tsétsêhéstâhese / Tsitsistas (Cheyenne proper) and Só’taeo’o / Só’taétaneo’o (better known as Suhtai or Sutaio), the latter may have joined the Tsétsêhéstâhese in the early 18th century. Their oral history relays that both tribal peoples are characterized, and represented by two cultural heroes or prophets who received divine articles from their god Ma’heo’o (″Sacred Being, God″, commonly in English Maheo, Mahiu, this is a post-missionary term, formerly the plural Ma’heono was used), which the Só’taeo’o called He’emo (″Goddess, Female Sacred Being, God″, equivalent to Ma’heo’o in the Tsétsêhéstâhese dialect).

The Tsétsêhéstâhese / Tsitsistas prophet Motsé’eóeve (Sweet Medicine Standing, Sweet Root Standing, commonly called Sweet Medicine) had received the Maahótse (in English known as Mahuts, a bundle of (Sacred) Arrows or the (Sacred) Arrows Bundle) at Nóávóse (″medicine(sacred)-hill″, name for Bear Butte, northwest of Rapid City, South Dakota),[15] which they carried when they waged tribal-level war[14][16][17] and were kept in the maahéome (Arrow Lodge or Arrow Tepee). He organized the structure of Cheyenne society, their military or war societies led by prominent warriors, their system of legal justice, and the Council of Forty-four peace chiefs, the latter was formed from four véhoo’o (chiefs or leaders) of the ten principal manaho (bands) and an additional four ″Old Man″ meeting to deliberate at regular tribal gatherings, centered around the Sun Dance.

Sweet Medicine is the Cheyenne prophet who predicted the coming of the horse, the cow, the white man and other new things to the Cheyenne. He was named for motsé’eonȯtse (sweetgrass), one of the sacred plant medicines used by many Plains peoples in ceremonies. The Maahótse (Sacred Arrows) are symbols of male power and the power of the Ésevone / Hóhkėha’e (Sacred Buffalo Hat) is female. The Sacred Buffalo Hat and the Sacred Arrows together form the two great covenants of the Cheyenne Nation. Through these two bundles, Ma’heo’o assures continual life and blessings for the people.

The Só’taeo’o prophet Tomȯsévėséhe (“Erect Horns”) had received the Ésevone (aka Is’siwun – “Sacred (Buffalo) Hat Bundle“) at Toh’nihvoos (″Stone Hammer Mountain″) near the Great Lakes in the present state of Minnesota. The Ésevone / Hóhkėha’e (Sacred Buffalo Hat) is kept in the vonȧhéome (old term) or hóhkėha’éome (new term) (“Sacred Hat Lodge, Sacred Hat Tepee”).

Erect Horns gave them the accompanying ceremonies and the Sun Dance. His vision convinced the tribe to abandon their earlier sedentary agricultural traditions to adopt nomadic Plains horse culture. They replaced their earth lodges with portable tipis and switched their diet from fish and agricultural produce, to mainly bison and wild fruits and vegetables. Their lands ranged from the upper Missouri River into what is now Wyoming, Montana, Colorado, and South Dakota.

The Ésevone / Hóhkėha’e (“Sacred Buffalo Hat”) is kept among the Northern Cheyenne and Northern Só’taeo’o. The Tséá’enōvȧhtse (″Sacred (Buffalo) Hat Keeper″ or ″Keeper of the Sacred (Buffalo) Hat″) must belong to the Só’taeo’o (Northern or Southern alike). In the 1870s tribal leaders became disenchanted with the keeper of the bundle demanded the keeper Broken Dish give up the bundle; he agreed but his wife did not and desecrated the Sacred Hat and its contents; a ceremonial pipe and a buffalo horn were lost. In 1908 a Cheyenne named Three Fingers gave the horn back to the Hat; the pipe came into possession of a Cheyenne named Burnt All Over who gave it to Hattie Goit of Poteau, Oklahoma who in 1911 gave the pipe to the Oklahoma Historical Society. In 1997 the Oklahoma Historal Society negotiated with the Northern Cheyenne to return the pipe to the tribal keeper of the Sacred Medicine Hat Bundle James Black Wolf.

STORIES

Coyote Dances With The Stars

Eagle War Feathers

Enough is Enough

Falling-Star (Northern Cheyenne)

How the Buffalo Hunt Began

How the First White Man Came to the Cheyennes

Origin of the Buffalo

Yellowstone Valley and the Great Flood

CULTURE AND LIFESTYLE

OCCUPATION

This Native American tribe lived as farmers, cultivating crops like squash, beans, and corn, also making pottery before migration. They also employed dog sleds and rafts as means of transport, residing in wigwams prepared from birch- bark and dirt or earth lodges. However, after they acquired horses from the Spanish, they gave up farming and became buffalo hunters, often trading animal hides in exchange for tobacco, fish or fruit. Adapting a nomadic existence, they naturally chose teepees for settling since these could be easily built or broken.

Today, teepees are only put up for fun and most live in modern houses.

Cheyenne Myth of the Golden Eagle

“When all living things were birds and animals, there was an old man who had power to heal the sick, and who could see into the future. This old man prayed to the creator so that his people could live in harmony with each other and with all life forces and the universe. This old man became the golden eagle, a messenger for his people to the creator. His talons were strung together and worn by a medicine man; his wing bones were made into whistles; and his feather and plumes were used in religious ceremonies and worn in remembrance of the Great Spirit.”

The Cheyenne lived in a valley next to a herd of buffalo. There was also a beautiful bird that also lived there and every time the warriors went to hunt the buffalo the bird would fly up and warn the buffalo that the Indians were coming to kill them and they would flee. Slowly the tribe was starving to death until a warrior decided to do something about it; so one night he went out on the prairie and dug a hole. He got into the hole and covered it with limbs and grass and then placed some bait on top. The next day the bird saw the bait and landed on top of the trap. The warrior grabbed the bird and tied a cord to its leg. He then threatened to punish the beautiful bird but the bird begged and pleaded that he would never warn the buffalo again so the warrior released him. The beautiful bird flew into the sky and then laughed at the warrior and said; “I lied to you, I lied to you. I am going to warn the buffalo.” The warrior then pulled the bird down from the sky by the cord and told the bird that this time he would be punished.

The warrior built a smoky fire and turned the beautiful bird over and over in the smoke and this is how we got the CROW.

CLOTHING AND ACCESSORIES

The Cheyenne clothing underwent several changes. The men initially wore breechcloths, leather leggings, and moccasins but switched over to plains war shirts commonly sported by the other Indians of the region. Similarly, the tall, feather headdresses put on by the Cheyenne Indian leaders were replaced by the long war bonnets of the Plains Indians. The clothing of women consisted of long buckskin dresses and high fringed boots. Their jewelry comprised of intricate necklaces and armbands. Much later, European costumes like cloth dresses and vests were adopted, and these were adorned with porcupine quills and fancy beading.

Today, most Cheyenne Indians wear modern clothes like jeans, using traditional dresses occasionally or in some ceremony.

FOOD HABITS

Before the acquisition of horses, when they were farmers, their diet consisted of buffalo or deer meat, corn, squash and beans. After leaving farming, they traded animal hides with other tribes to get fish, corn, tobacco and fruits. To overcome the scarcity of food in the harsh winter months, they traded cotton, hemp, and other medicinal plants with other tribes in exchange for food.

MARRIAGE AND FAMILY STRUCTURE

The Cheyenne tribe had an extended family that consisted of parents, children, and grandparents, all of whom stayed close together and shared economic resources.

Most of the tribal marriages were monogamous, and a young Cheyenne normally agreed to get married only after he had proved himself either by acquiring horses or securing a reputed position in war. As a result, courtship often carried on for years.

Source: Jack Powell

Other Cheyenne Home Pages

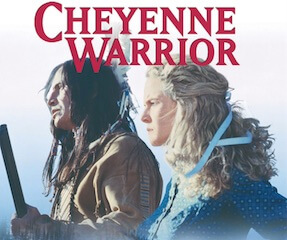

Cheyenne Warrior

(Film by Michael B. Druxman)

Links to Other Cheyenne Home Pages

Tse-tsehese-staestse

(Cheyenne {shy-an’} )

Tse-tsehese-staestse is what the Cheyenne call themselves. The word Cheyenne was believed to come from the French word chien for dog. The French traders called these people this because of the famous dog soldiers of the Cheyenne nation. This is erroneous. The now accepted etymology of the word Cheyenne is that it is the anglicized word Shyhela, which is Sioux.

The Cheyenne people are the most western branch of the Algonquian people. They originally came from the great lakes area. There are many theories about why the Cheyenne moved from the great lakes area. Most of them involve competition in the area with the Ojibwe, Ree, and Mandan. They originally lived as sedentary farmers in northeastern Minnesota, from which they began migrating westward in the late 1600s; they later settled along the Cheyenne River of North Dakota. Dislodged ca.1770, they gradually moved southwestward; when encountered (1804) by the Lewis and Clark expedition, they were living as nomadic buffalo-hunters in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

Religiously, the Cheyenne were guided to the plains area by Maheo. They also were sent a prophet named Sweet Medicine who helped organize themselves, and developed a code to live by. He gave them their first sacred item — the four sacred arrows. It was at this point the Cheyenne became a powerful force to be reckoned with. Their hunting territory extended from the Platte River to what is now eastern Montana. A southern group also had hunting grounds around the Arkansas River. Another group of people known as the Sohtaio also joined the Cheyenne. It is said that these two groups of people were one day fighting, when the Cheyenne overheard the Sohtaio speak amongst themselves. To their surprise, they could understand the people. Peace was quickly pursued and these people have lived with the Cheyenne ever since.

In 1832 the tribe split into two branches, the northern Cheyenne, who inhabited the area around the Platte River, and the southern Cheyenne, who lived near the Arkansas River. The Cheyenne were constantly at war with the Crow until 1840, when an alliance was formed with the KIOWA, APACHE, and COMANCHE. From 1857 to 1879 they fought white settlers and the U.S. Army, especially after the brutal Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, in which an estimated 500 Cheyenne were killed. The Cheyenne played an important role in the defeat of Gen. George Custer and the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn (1876).

The Cheyenne moved frequently: In South Dakota they lived along the Cheyenne River and in the Black Hills. But bands of their tribe were known in every western state. Before 1700 a large group settled on the Minnesota River, and some Cheyennes visited LaSalle’s Fort in Illinois in 1680. Between 1780 and 1790, their settlements were attacked by Chippewas while Cheyenne men were away hunting. Escapees settled on the Missouri River near other Cheyennes.

(known in Cheyenne. either as Notameohmésêhese or Notameohmésėhétaneo’o meaning “Northern Eaters” or simply as Ohmésêhese / Ôhmésêheseo’o meaning “Eaters”)

- Notameohmésêhese / Notameohmésėhétaneo’o proper (“Northern Eaters”, also simply known as Ȯhmésėhese / Ôhmésêheseo’o or Omísis – “Eaters”, went by this names because they were known as great hunters and therefore had a good supply of meat to feed their people, most populous Cheyenne group, inhabited land from the northern and western Black Hills (Mo’ȯhtávo’honáéva – ″black-rock-Location″) toward the Powder River Country (Páeo’hé’e – ″gunpowder river″ or ″coal river″), often they were accompanied by their Totoemanaho and Northern Só’taeo’o kin, had through intermarriages close ties to Lakota, today they – along with the Northern Só’taeo’o – are the most influential among the Northern Cheyenne)

- Northern Oévemanaho / Oivimána (Northern Oévemana – “Northern Scabby“, “Northern Scalpers”, now living in and around Birney, Montana (Oévemanâhéno – ″scabby-band-place″) near the confluence of the Tongue River and Hanging Woman Creek in the southeastern corner of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation)

- Northern Só’taeo’o / Só’taétaneo’o (Suhtai or Sutaio, married only other Só’taeo’o (Northern or Southern alike) and camped always separate from the other Cheyenne camps, maintained closest ties to the Notameohmésêhese band, lived in the northern and western Black Hills (Mo’ȯhtávo’honáéva – ″black-rock-Location″) and roamed together with their Notameohmésêhese and Totoemanaho kin also in the Powder River Country (Páeo’hé’e), remained north of the Platte River, where they gained higher band numbers than their southern kin because of better Northern hunting and grass, now living in and around Birney, Montana (Oévemanâhéno – ″scabby-band-place″), today they – along with the Notameohmésêhese – are the most influential among the Northern Cheyenne)

- first band

- second band

Lesser northern bands (not represented in the Council of Forty-Four):

- Anskówînîs / Anskowinis (“Narrow Nose”, “narrow-nose-bridge”, named after their first chief, properly named Broken Dish, but nicknamed Anskówǐnǐs, they separated from the Ôhmésêheseo’o on account of a quarrel)

- Moktavhetaneo / Mo’ȯhtávėhetaneo’o (Mo’ôhtávêhetane – “Black skinned Men”, “Ute-like Men”, because they had darker skin than other Cheyenne, they looked more like the Utes to their Cheyenne kin, also meaning ″Mountain Men″, maybe descended from Ute (Mo’ȯhtávėhetaneo’o) captives, living today in the Lame Deer, Montana (Mo’ȯhtávȯheomenéno – ″black-lodge-place″) district on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation; because Lame Deer as tribal and government agency headquarters was also the place where rations were given out it is also known as Meaveʼhoʼeno – ″the giving place″ or ″giving-whiteman-place″)

- Ononeo’o / Ononeo (“Arikara People” or ″Ree Band″, because they were through intermarriage of mixed Cheyenne-Arikara and Mandan heritage, formerly strong associated with the mixed Cheyenne-Lakota Masikota band, sometimes sought of as a Masikota subband, today they live in the nonofficial Rosebud/Ree district (Ónoneo’o), politically part of the Muddy creammmmm district, between Busby and Muddy Creek, some are also present in the Lame Deer district)

- Totoemanaho / Totoimana (Totoemana, Tútoimanáh – “Backward Clan”, “Shy Clan” or “Bashful Clan”, also translated as ″Reticent Band″, and ″Unwilling Band″, so named because they prefer to camp by themselves, lived in the northern and western Black Hills (Mo’ȯhtávo’honáéva – ″black-rock-Location″) and along the Tongue River (Vétanovéo’hé’e – ″Tongue River″), roamed together with their Notameohmésêhese and Northern Só’taeo’o kin also in the Powder River Country (Páeo’hé’e), had through intermarriages close ties to Lakota, now centered in and around Ashland, Montana (Vóhkoohémâhoéve’ho’éno, formerly called Totoemanáheno) immediately east of the boundary of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation)

- Vóhpoométaneo’o / Woxpometaneo (Voxpometaneo – “White River People”, ″White River Cheyenne″, named for the White River (Vóhpoome) near Pine Ridge in South Dakota, also named after a large extended family as Wóopotsît or Wóhkpotsit – “White Wolf”, ″White Crafty People″, the majority joined their Cheyenne kin and settled 1891 south of Kirby, Montana near the headwaters of the Rosebud Creek and are now centered in and around Busby, Montana (Vóhpoométanéno) on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, some stayed on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation with their Oglala Lakota kin and are known as Tsėhésė-ho’óhomo’eo’o – ″Cheyenne-Sioux″).

Southern Cheyenne (known in Cheyenne as Heévâhetaneo’o meaning “Roped People” – after the most populous band, also commonly known as Sówoniá – “the Southern People”).

- Heévâhetaneo’o / Hevhaitaneo proper (Hévhaitanio – “Haire Rope Men”, “Hairy People”, also ″Fur Men″, were close affiliated to Arapaho, known as great warriors and noted among the Cheyenne as the best horse tamers and horse raiders from surrounding tribes – especially from the horse-rich Kiowa (Vétapâhaetó’eo’o – ″greasy-wood-ones″) and Comanche (Šé’šenovotsétaneo’o – ″snake people″) to the south, they initiated in 1826 under their Chief Yellow Wolf (Ho’néoxheóvaestse) – together with some Arapaho – the migration of some Cheyenne bands south of the Platte River (Meneo’hé’e – ″Moon Shell River″, North Platte River was known by the same name) toward the Arkansas River (Mótsėsóoneo’hé’e – ″Flint River″) and the establishment of Bents Fort, their tribal lands were between that of the Southern Oévemanaho in the west, the Wotápio in the east and the Dog Soldiers and Hesé’omeétaneo’o in the north, heavy cholera losses in 1849, perhaps half of the survivors were lost at Sand Creek, including the chiefs Yellow Wolf and Big Man; they are today predominant among the Southern Cheyenne)

- Hesé’omeétaneo’o / Hisiometaneo (Hisíometanio or Issiometaniu – “Ridge People/Men” or ″Hill Band″, also given as ″Pipestem (River) People″, originally part of the Heévâhetaneo’o, also had close ties with the Oglala and Sičháŋǧu (Brulé) Lakota, first living just south of the Masikota along the Niobrara River north of the North Platte River in Nebraska, later they moved south into the hill country along the Upper Smoky Hill River and north of the Upper Arkansas River in Colorado – in lands mostly west of the closely associated Southern Só’taeo’o and Dog Soldiers band and north of the Southern Oévemanaho and Heévâhetaneo’o, ranged sometimes with Comanche south onto the Staked Plains, under chief White Antelope at Sand Creek they experienced heavy losses)

- Heviksnipahis / Iviststsinihpah (“Aorta People” or “Burnt Aorta People”; as caretakers for the Sacred Arrows, they were also considered as the Tsétsêhéstâhese / Tsitsistas proper or known to the other bands as ″Arrow People″, originally living along the forks of the Cheyenne River and in the eastern Black Hills in western Wyoming, they moved between 1815 and 1825 south to the forks of the North and South Platte River (Vétaneo’hé’e – ″Fat River″ or ″Tallow River″), which made sense geographically since their lands was a central location for all bands and convenient for the performance of the annual ceremonies; later, they moved further south and ranged between the Dog Soldiers band in the north, the Oo’kóhta’oná in the southeast, the Hónowa and Wotápio in the south)

- Hónowa / Háovȯhnóvȧhese / Nėstamenóoheo’o (Háovôhnóva, Hownowa, Hotnowa – “Poor People”, also known as ″Red Lodges People″, lived south of the Oo’kóhta’oná and east of the Wotápio)

- Southern Oévemanaho / Oivimána (Southern Oévemana – “Southern Scabby”, “Southern Scalpers”, originally part of the Heévâhetaneo’o, were also close affiliated to Arapaho, moved together with the Heévâhetaneo’o under Chief Yellow Wolf in 1826 south of the Platte River to the Arkansas River, ranged south of the Hesé’omeétaneo’o and west of the Heévâhetaneo’o, led by War Bonnet they lost at Sand Creek about half their number, now living near Watonga (Tséh-ma’ėho’a’ē’ta – ″where there are red (hills) facing together″, also called Oévemanâhéno – ″scabby-band-place″) and Canton, Blaine County, on lands of the former Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation in Oklahoma)

- Masikota (“Crickets”, “Grasshoppers”, ″Grey Hair(ed) band″, ″Flexed Leg band″ or ″Wrinkled Up band″, perhaps a Lakotiyapi word mazikute – “iron (rifle) shooters”, from mazi – “iron” and kute – “to shoot”, mixed Cheyenne-Lakota band, were known by the latter as ‘Sheo’, lived southeast of the Black Hills along the White River (Vóhpoome), intermarried with Oglala Lakota and Sičháŋǧu Oyáte (Brule Lakota), was the first group of the tribal unit on the Plains, hence their name First Named, almost wiped out by the cholera epidemic of 1849, joined afterwards the military society Dog Soldiers (Hotamétaneo’o), which took their place as a band in the Cheyenne tribal circle, not present at Sand Creek in 1864, important at Battle of Summit Springs of 1869)

- Oo’kóhta’oná / Ohktounna (Oktogona, Oktogana, Oqtóguna or Oktoguna – “Bare Legged”, “Protruding Jaw”, referring to the art of dancing the Deer Dance before they were going to war, formerly strong associated with the mixed Cheyenne-Lakota Masikota band, sometimes sought of as a Masikota subband, living north of the Hónowa and south of the Heviksnipahis, almost wiped out by an cholera epidemic in 1849, perhaps also joining the Dog Soldiers).

- Wotápio / Wutapai (from the Lakotiyapi word Wutapiu: – “Eat with Lakota-Sioux”, “Half-Cheyenne”, “Cheyenne-Sioux”, originally a band of Lakota Sioux which joined the Southern Cheyenne, by 1820 they had moved south to the Arkansas River in Colorado, where they lived and camped together with their Kiowa allies, through intermarriage becoming a mixed Cheyenne-speaking and identifying hybrid Cheyenne-Kiowa band with Lakota origin, their hunting lands were between the Hónowa in the east, the Heévâhetaneo’o to the west, and the Heviksnipahis to the north, hardest hit by the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864)

- Southern Só’taeo’o / Só’taétaneo’o (Suhtai or Sutaio, married only other Só’taeo’o (Northern or Southern alike) and always camped separately from the other Cheyenne camps, maintained closest ties to the Hesé’omeétaneo’o band, joined with the emerging Dog Soldiers band lands along the Smoky Hill River (Mano’éo’hé’e – ″gather(timber) river″), Saline (Šéstotó’eo’hé’e – “Cedar River”) and Solomon Rivers (Ma’xêhe’néo’hé’e – “turkey-creek”), in north-central Kansas, their favourite hunting grounds were north of the Dog Soldiers along the upper subbasins of the Republican River (Ma’êhóóhévâhtseo’hé’e – ″Red Shield River″, so named because there gathered the warriors of the Ma’ėhoohēvȧhtse (Red Shield Warriors Society)) especially along the Beaver Creek, which was although a spiritual place, the Hesé’omeétaneo’o mostly ranged west and northwest of them)

- first band

- second band

lesser southern bands (not represented in the Council of Forty-Four):

- Moiseo / Moiseyu (Monsoni – “Flint-Men”, called after the Flintmen Society (Motsêsóonetaneo’o), were also called Otata-voha – “Blue Horses”, after Blue Horse, the first leader of the Coyote Warriors Society (O’ôhoménotâxeo’o), both were branches of the Fox Warriors Society (Vóhkêséhetaneo’o or Monêsóonetaneo’o), one of the four original Cheyenne military societies, also known as ″Flies″, originally a Sioux band from Minnesota, the greater part departed from the Cheyenne about 1815 joining Sioux bands in Minnesota, the remaining were associated strongly with / or joined the Wotápio)

- Ná’kuimana / Nakoimana (Nakoimanah – “Bear People”)

The Heviksnipahis (Iviststsinihpah, also known as the Tsétsêhéstâhese / Tsitsistas proper), Heévâhetaneo’o (Hevhaitaneo), Masikota (in Lakotiyapi: Sheo), Omísis (Ôhmésêheseo’o, the Notameohmésêhese proper), Só’taeo’o / Só’taétaneo’o (Suhtai or Sutaio, Northern and Southern), Wotápio (Wutapai), Oévemanaho (Oivimána or Oévemana, Northern and Southern), Hesé’omeétaneo’o (Hisiometaneo or Issiometaniu), Oo’kóhta’oná (Ohktounna or Oqtóguna) and the Hónowa (Háovȯhnóvȧhese or Nėstamenóoheo’o) were the ten principal bands that had the right to send four chief delegates representing them in the Council of Forty-Four.

After the Masikota and Oo’kóhta’oná bands had been almost wiped out through a cholera epidemic in 1849, the remaining Masikota joined the Dog Soldiers warrior society (Hotamétaneo’o). They effectively became a separate band and in 1850 took over the position in the camp circle formerly occupied by the Masikota. The members often opposed policies of peace chiefs such as Black Kettle. Over time, the Dog Soldiers took a prominent leadership role in the wars against the whites. In 1867, most of the band were killed by United States Army forces in the Battle of Summit Springs.

Due to an increasing division between the Dog Soldiers and the council chiefs with respect to policy towards the whites, the Dog Soldiers became separated from the other Cheyenne bands. They effectively became a third division of the Cheyenne people, between the Northern Cheyenne, who ranged north of the Platte River, and the Southern Cheyenne, who occupied the area north of the Arkansas River.

Today the Cheyenne occupy two reservations, one at Tongue River, Mont., and the other in southwestern Oklahoma. Their population was about 7,500 in 1989.

Black Kettle Museum/Washita Battlefield

Box 252 Cheyenne, OK 73628

Dedicated to Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle

and

Site of the 1868 “Battle of the Washitas“

between General George Custer’s

405-497-3929

Cheyenne People: History, Culture, and Current Status

The Cheyenne people or, more properly, the Tsétsêhéstaestse, are a Native American group of Algonquin speakers whose ancestors came from the Great Lakes region of North America. They are known for their partially successful resistance to the United States government’s attempt to move them to a reservation far from their home territories. The Cheyenne people are Plains Algonquian speakers whose ancestors lived in the Great Lakes region of North America. They began moving westward in the 16th or 17th century. In 1680, they met the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (1643–1687) on the Illinois River, south of what would become the city of Peoria. Their name, “Cheyenne,” is a Sioux word, “Shaiena,” which roughly means “people who speak in a strange tongue.” In their own language, they are Tsétsêhéstaestse, sometimes spelled Tsistsistas, meaning “the people.” Oral history, as well as archaeological evidence, suggests that they moved into southwest Minnesota and the eastern Dakotas, where they planted corn and built permanent villages. Possible sites have been identified along the Missouri River, and they certainly lived at the Biesterfeldt site on the Sheyenne River in eastern North Dakota between 1724 and 1780. An outlier report is that of a Spanish official in Santa Fe, who as early as 1695 reported seeing a small group of “Chiyennes.” Around 1760, while living in the Black Hills region of South Dakota, they met the Só’taeo’o (“People Left Behind,” also spelled Suhtaios or Suhtais), who spoke a similar Algonquian language, and the Cheyenne decided to align with them, eventually growing and expanding their territory.

The Cheyenne tribe originally lived in the upper Mississippi River valley but early in the 18th century they migrated to the Great Plains. Once the Cheyenne tribe obtained good supplies of horses they became expert buffalo hunters. In the 19th century the Cheyenne tribe split into two sections. One group moved south onto the Central Plains whereas the other group remained in Montana, Wyoming and South Dakota. Those in the north became involved in wars with the Sioux. The Cheyenne group in the south came into conflict with the Apache, Comanche and Kiowa. During these wars Cheyenne warriors developed a reputation for bravery. In 1867 the Cheyenne joined forces with the Sioux to attack soldiers trying to protect the Bozeman Trail. On 2nd August, several thousand Sioux and Cheyenne attacked a wood-cutting party led by Captain James W. Powell. The soldiers had recently been issued with Springfield rifles and this enabled them to inflict heavy casualties on the warriors. After a battle that lasted four and a half hours, the Native Americans withdrew. Six soldiers died during the fighting and Powell claimed that his men had killed about 60 warriors.

Spiritual Practices

Cheyenne religion recognized two principal deities, the Wise One Above and a God who lived beneath the ground. In addition, four spirits lived at the points of the compass. The Cheyenne were among the Plains tribes who performed the sun dance in its most elaborate form. They placed heavy emphasis on visions in which an animal spirit adopted the individual and bestowed special powers upon him so long as he observed some prescribed law or practice. Their most venerated objects, contained in a sacred bundle, were a hat made from the skin and hair of a buffalo cow and four arrows – two painted for hunting and two for battle. These objects were carried in war to insure success over the enemy. The Cheyenne practiced shamanism – dance, medicine.

Comments

Post a Comment