Mythologies of the Ouled Naïl Tribe

The Ouled Naïl (/ˌuːlɛd ˈnaɪl/; Arabic: أولاد نايل) are an Arab tribal confederation living in the Ouled Naïl Range, Algeria. They are found mainly in Bou Saâda, M'Sila and Djelfa, but there is also a significant number of them in Ghardaïa. The oral lore of the Ouled Naïl people claims ancient Arab descent from tribes that arrived in the area about a thousand years ago. They trace their origin back to Sidi Naïl, an Arab marabout and sharif (descendent of Muhammad) who settled in central Algeria in the 16th century. Some traditions trace their ancestry to the Banu Hilal of Najd, who came to the highlands through El Oued, Ghardaia. The Ouled Naïl are seminomadic or nomadic people living in the highlands of the range of the Saharan Atlas to which they gave their name. The town of Djelfa has been traditionally an important market and trade centre for the Ouled Naïl, especially for their cattle. The town has cold and long winters with temperatures averaging 4 °C. In recent years Djelfa Province has become one of the most populated provinces of the Hauts-Plateaux with a population of 1,164,870. The Ouled Naïl have traditionally reared cattle as nomads in their mountain grasslands, as well in the northern Hodna region and the Dayas in the south. When they are nomadic they live in black-and-red striped tents, but they also used to live in dechra, or non fortified villages, or in ksour, fortified ones. Cereal cultivation is possible in the mountain heights, although with rather irregular results. They rarely were able to cultivate date palms in the heights but obtained dates from other areas by trading, especially in Bou Saâda located at the feet of the northern end of the mountain range. Despite the harsh conditions of the dry and cold highlands where they live, this ethnic group has managed to fare fairly well in their traditional environment along the centuries. However, the odd years of drought and years with prolonged, cold winters are disastrous for the Ouled Nail; in 1944, and again in 1947, when weather conditions were especially rough, about 50% of their livestock died and famines followed. The Ouled Naïl tribe originated a style of music, sometimes known as Bou Saâda music after the town near their homeland. In belly dancing, the term refers to a style of dance originated by the Ouled Naïl, noted for their way of dancing. Although their primary roles and activities in their rural milieu were connected with animal farming, most women trained in the art of dance and song from childhood. Thus for Ouled Naïl females the practice of leaving their ancestral home and settling in a nearby desert town as entertainers was common. This was especially so in times of disaster and famine, when a woman had relative freedom to fend for herself in order to survive, save money and improve her future economic status.

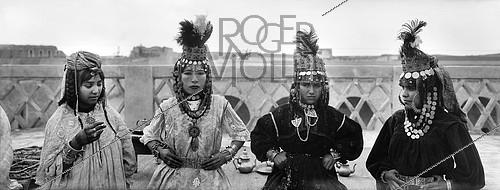

Centuries before Betty Friedan and the sexual revolution challenged social mores in the West, the women of the Ouled Nail in Algeria enjoyed the freedom to earn their own fortunes, choose lovers and engage in sexual relationships outside of marriage in a society that placed no shame on these choices – and indeed valued these activities as important contributions to the overall community. An Amazigh tribe, the Ouled Nail lived high in the Atlas Mountains. The nomads converted to Islam in the 7th century but maintained their unique culture, traditions and identity into the 20th century. Perhaps the most widely recognized of these traditions was that of the Nailiyat dancers. Nailiyat women left their rural mountain abodes seasonally, descending into the larger cities and oasis towns to work as professional dancers and hostesses. Not all Nailiyat women were dancers, but the practice was usually passed down within families, where girls learned the dance and other skills from older relatives. While women from nearby tribes engaged in similar practices in times of economic hardship, such as upon being orphaned or widowed, it seems it was only the Ouled Nail who freely chose and proudly perpetuated the tradition by handing it down to their children, who began performing around the age of 12. The men remained behind at home, so during their seasonal stays in the city the dancers formed strong women-centered communities in which the mothers, aunts and grandmothers played chaperone and kept house while the younger women performed and entertained. Men were invited into this cocoon as friends, business associates, lovers or clients, but their presence was temporary and somewhat peripheral. It was the women around whom this life was built and revolved, and it was the women who ordered it. Dressed in lavish layers of silks and other opulent fabrics, the Nailiyat braided their hair into long, thick plaits, tattooed their faces with symbols of their tribe and decorated their hands and feet with henna. Elaborate gold and silver jewelry and headdresses made from coins earned in their trade advertised their success and desirability, and heavy bracelets fashioned with large spikes were said to serve as weapons for protection. While wearing one’s wealth may have ostensibly kept it in sight and safe, it also meant people with ill intentions knew exactly what they might stand to gain. Stories abound of Nailiyat being murdered for the jewelry they wore.

Ouled Nail, with her robe of vivid crimson embroidered in gold, her soft silk veil of the palest blue…the wide gold girdle with its innumerable chains and pendants, the necklaces of coins, the bracelets of silver and gold, and the crown-like head-dress, is the personification of the gorgeous East. – Frank Edward Johnson, “Here and There in Northern Africa” (The National Geographic Magazine, January 1914) The Ouled Nail (pronounced “will-ed nah-eel”) were a Berber tribe who inhabited the Atlas Mountains of Algeria; their origins are lost to history, and though they were converted to Islam in the 7th and 8th centuries CE along with the other Berbers, they retained a number of distinctive characteristics which set them apart until well into the 20th century. Chief among these was the status of their women, or Nailiyat; not only were they free from purdah, in adolescence they actually went down into the cities unescorted by men and worked for a time as dancers and prostitutes in order to amass a personal fortune with which to purchase property at home, and only after they had done this would they seek marriage. The Nailiyat were thus not only remarkably independent by the standards of tribal cultures or Muslims, but even by the traditional standards of European cultures; they enjoyed a freedom unknown by any but the wealthiest, boldest women before the “sexual revolution”, and indeed greater than that of many “liberated” women to this very day. The Nailiyat were not forced or expected to practice dancing and harlotry, but it was more common than not and the trade ran in families. Daughters learned dancing and the erotic arts from their mothers, and about the age of 12 started travelling down to the cities for part of the year, accompanied by their mothers, grandmothers or aunts (who not only advised and helped them, but also kept house). They typically returned home seasonally, and as they grew older and more experienced they might sometimes make the trips with sisters or cousins of similar age instead, or later graduate to escorting younger relatives. After five to fifteen years of work (depending on the individual’s aspirations and level of success) a Nailiya usually returned home permanently, purchased a house and garden, and began to accept suitors; after marriage she settled down to the normal domestic role and marital fidelity which are traditionally expected of women throughout the world, and when she had daughters of her own she trained them and accompanied them down to the cities in their turn. Women of the Ouled Abdi and Ouled Daoud tribes sometimes worked as dancers and whores as well, but unlike the Ouled Nail they only did so after being orphaned, divorced, widowed or otherwise cut off from financial support.

Belly dance, an exotic, sensual art of body movement has made its mark all over the world. From the growing trends in America today, this art has blossomed in the Middle East and surrounding areas reaching far across the waters and into our own backyards. This kind of dance has been coined as a tool of seduction and often mistaken for means of prostitution. As many would like to suggest otherwise, tucked in the mountains of Algeria, this dance was precisely that: a way for women to make money by dancing and then selling their bodies for a living, a tradition long past the ages. The Ouled Nail (pronounced “ooh-led nile”), a dance term in the realm of folklore, is a tribe living in the mountains in Algeria. From an early age, the women were taught about dance movements and sexuality. They traveled from village to village, primarily in the Sahara, and some of these destinations still quite notorious to this day. After caravanning throughout the Sahara, they closed out the season by returning to their village until the next season arose. When the women have raised enough dowry funds from their travels, they retired back to the village to marry a suitable husband. The husband did not take shame in her former profession, though the married woman would never dance publicly again. The styles of dance of these women were heavily symbolic, draped in earthiness and sexuality, containing many snake arms and undulations. The women danced often in pairs, but only on special occasions. When all lined up, the women would stand with their shoes placed in front of them and when one dancer tires, another would take her place in order to keep a pair always together in the dance space. As the performance progressed, the women would disappear behind a screen and emerge moments later in only their jewelry and headdresses, which obviously left little to the imagination.

The Ouled Naïl (/ˌuːlɛd ˈnaɪl/; Arabic: أولاد نايل) are a tribe and a tribal confederation living in the Ouled Naïl Range, Algeria. They are found mainly in Bou Saâda, M'Sila and Djelfa, but there is also a significant number of them in Ghardaïa Province, beyond their ancestral region. The oral lore of the Ouled Naïl people claims ancient Arab descent from tribes that arrived in the area about a thousand years ago. Some traditions trace their ancestry to the Banu Hilal of Hejaz, who came to the highlands through El Oued, Ghardaia, while others claim that they are direct descendants of Idris I. Current research confirms that the Ouled Naïl have a highly Arabized Berber tribal society. The Ouled Naïl are seminomadic or nomadic people living in the highlands of the range of the Saharan Atlas to which they gave their name. The town of Djelfa has been traditionally an important market and trade centre for the Ouled Naïl, especially for their cattle. The town has cold and long winters with temperatures averaging 4 °C. In recent years Djelfa Province has become one of the most populated provinces of Algeria with a population of 1,164,870. The Ouled Naïl have traditionally reared cattle as nomads in their mountain grasslands, as well in the northern Hodna region and the Dayas in the south. When they are nomadic they live in black-and-red striped tents, but they also used to live in dechra, or non fortified villages, or in ksour, fortified ones. Cereal cultivation is possible in the mountain heights, although with rather irregular results. They rarely were able to cultivate date palms in the heights but obtained dates from other areas by trading, especially in Bou Saâda located at the feet of the northern end of the mountain range. Despite the harsh conditions of the dry and cold highlands where they live, this ethnic group has managed to fare fairly well in their traditional environment along the centuries. However, the odd years of drought and years with prolonged, cold winters are disastrous for the Ouled Nail; in 1944, and again in 1947, when weather conditions were especially rough, about 50% of their livestock died and famines followed. The Ouled Naïl tribe originated a style of music, sometimes known as Bou Saâda music after the town near their homeland. In belly dancing, the term refers to a style of dance originated by the Ouled Naïl, noted for their way of dancing.

Images

Comments

Post a Comment