George Bent – Cheyenne-American Soldier & Leader

Let me be a free man, free to travel, free to stop, free to work, free to trade where I choose, free to choose my own teachers, free to follow the religion of my fathers, free to talk, think, and act for myself — and I will obey every law or submit to the penalty. Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekht has spoken for his people.

–– Chief Joseph

Like other tribes too large to be united under one chief, the Nez Perce tribe of Indians was composed of several bands, each distinct in sovereignty. It was a loose confederacy. Joseph and his people occupied the Imnaha or Grande Ronde Valley in Oregon, which was considered perhaps the finest land in that part of the country. When the last treaty was entered into by some of the bands of the Nez Perce, Joseph’s band was at Lapwai, Idaho, and had nothing to do with the agreement. The elder chief, in dying, counseled his son, who was not more than twenty-two or twenty-three years of age, never to part with their home, assuring him that he had signed no papers. These peaceful, non-treaty Indians did not even know what land had been ceded until the agent read them the government order to leave. Of course, they refused. You and I would have done the same.

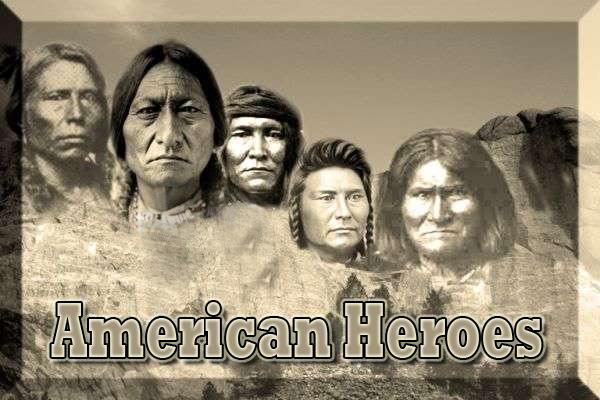

Leadership can entail many things. For Native Americans, caring for their people has meant not only securing food and shelter, or carrying forward spiritual teachings and cultural traditions, or helping to keep the peace internally and with neighbors. Ever since European settlers began arriving in the 16th century, leadership for America’s Indigenous peoples has disproportionately involved fighting to simply exist. Some American Indian leaders sought to broker treaties. And when that didn’t work, they went to war—to protect their ancestral lands, their hunting grounds and their ways of life. Some gave their lives in the struggle. In later years, leaders have served not only as chiefs but as activists and organizers, calling attention to the ongoing discrimination and oppression of Indigenous peoples. Issues have ranged from broken treaties and tribal sovereignty to voting rights and forced sterilization. Though nowhere near complete, this list details many influential Native American leaders, both men and women, who made their mark in history.

Red Jacket (known as Otetiani [Always Ready] in his youth and Sagoyewatha [Keeper Awake] Sa-go-ye-wa-tha as an adult because of his oratorical skills) (c. 1750 – January 20, 1830) was a Seneca orator and chief of the Wolf clan, based in Western New York. On behalf of his nation, he negotiated with the new United States after the American Revolutionary War, when the Seneca as British allies were forced to cede much land following the defeat of the British; he signed the Treaty of Canandaigua (1794). He helped secure some Seneca territory in New York state, although most of his people had migrated to Canada for resettlement after the Paris Treaty. Red Jacket's speech on "Religion for the White Man and the Red" (1805) has been preserved as an example of his great oratorical style. Red Jacket's birthplace has long been a matter of debate. Some historians claim he was born about 1750 at Kanadaseaga, also known as the Old Seneca Castle. Present-day Geneva, New York, developed near here, at the top of Seneca Lake. Others believe he was born near Cayuga Lake and present-day Canoga. Others say he was born south of present-day Branchport, at Keuka Lake near the mouth of Basswood Creek. It is known that he grew up with his family at Basswood Creek, and his mother was buried there after her death. The Iroquois had a matrilineal kinship system, with inheritance and descent figured through the maternal line. Red Jacket was considered to be born into his mother's Wolf Clan, and his social status was based on her family and clan. He was taught by his mother at a young age that truth was a powerful weapon. Red Jacket lived much of his adult life in Seneca territory in the Genesee River Valley in western New York. In the later years of his life, Red Jacket moved to Canada for a short period of time. He and the Mohawk chief Joseph Brant became bitter enemies and rivals before the American Revolutionary War, although they often met together at the Iroquois Confederacy's Longhouse. During the war, when most of both the Seneca and Mohawk were allies of the British, Brant contemptuously referred to Red Jacket as "cow killer". He alleged that at the Battle of Newtown in 1779, Red Jacket killed a cow and used the blood as evidence to claim he had killed an American rebel.

Tecumseh ( tih-KUM-sə, -see; c. 1768 – October 5, 1813) was a Shawnee chief and warrior who promoted resistance to the expansion of the United States onto Native American lands. A persuasive orator, Tecumseh traveled widely, forming a Native American confederacy and promoting intertribal unity. Even though his efforts to unite Native Americans ended with his death in the War of 1812, he became an iconic folk hero in American, Indigenous, and Canadian popular history. Tecumseh was born in what is now Ohio at a time when the far-flung Shawnees were reuniting in their Ohio Country homeland. During his childhood, the Shawnees lost territory to the expanding American colonies in a series of border conflicts. Tecumseh's father was killed in battle against American colonists in 1774. Tecumseh was thereafter mentored by his older brother Cheeseekau, a noted war chief who died fighting Americans in 1792. As a young war leader, Tecumseh joined Shawnee Chief Blue Jacket's armed struggle against further American encroachment, which ended in defeat at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 and with the loss of most of Ohio in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. In 1805, Tecumseh's younger brother Tenskwatawa, who came to be known as the Shawnee Prophet, founded a religious movement that called upon Native Americans to reject European influences and return to a more traditional lifestyle. In 1808, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa established Prophetstown, a village in present-day Indiana, that grew into a large, multi-tribal community. Tecumseh traveled constantly, spreading the Prophet's message and eclipsing his brother in prominence. Tecumseh proclaimed that Native Americans owned their lands in common and urged tribes not to cede more territory unless all agreed. His message alarmed American leaders as well as Native leaders who sought accommodation with the United States. In 1811, when Tecumseh was in the South recruiting allies, Americans under William Henry Harrison defeated Tenskwatawa at the Battle of Tippecanoe and destroyed Prophetstown.

“I am a red man. If the Great Spirit had desired me to be a white man he would have made me so in the first place. He put in your heart certain wishes and plans, in my heart he put other and different desires. Each man is good in his sight. It is not necessary for Eagles to be Crows. We are poor… but we are free. No white man controls our footsteps. If we must die…we die defending our rights.” – Sitting Bull Hunkpapa Sioux (Tatanka Iyotake).

It is not easy to characterize Sitting Bull, of all Sioux chiefs most generally known to the American people. There are few to whom his name is not familiar, and still fewer who have learned to connect it with anything more than the conventional notion of a bloodthirsty savage. The man was an enigma at best. He was not impulsive, nor was he phlegmatic. He was most serious when he seemed to be joking. He was gifted with the power of sarcasm, and few have used it more artfully than he. His father was one of the best-known members of the Unkpapa band of Sioux. The manner of this man’s death was characteristic. One day, when the Unkpapa were attacked by a large war party of Crow, he fell upon the enemy’s war leader with his knife. In a hand-to-hand combat of this sort, we count the victor as entitled to a war bonnet of trailing plumes. It means certain death to one or both. In this case, both men dealt a mortal stroke, and Jumping Buffalo, the father of Sitting Bull, fell from his saddle and died in a few minutes. The other died later from the effects of the wound.

Born to the Lemhi tribe of Shoshone Indians in present-day Idaho in about 1788, Sacagawea would grow up to be a near-legendary figure for her indispensable role in the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The daughter of a Shoshone chief, she was kidnapped after a battle with Hidatsa Indians that resulted in the deaths of four Shoshone warriors and several women and children. She was only about ten years old. Taken back to the Hidatsa village near present-day Washburn, North Dakota, she quickly assimilated into the Hidatsa culture and learned to speak their language. Sometime later, Sacagawea was sold to Toussaint Charbonneau, a French Canadian trapper, as his wife. In the winter of 1804, the Lewis and Clark Expedition were encamped near several Hidatsa villages to build Fort Mandan in North Dakota. While there, they interviewed several trappers who could assist as guides and interpreters. They quickly hired Charbonneau as an interpreter when they discovered his wife spoke the Shoshone language, knowing they would need the help of the Shoshone tribes at the headwaters of the Missouri River. By the time Charbonneau and his wife joined the expedition at Fort Mandan, Sacagawea was pregnant. The expedition welcomed her, for her language skills, with William Clark noting in his journal, “A woman with a party of men is a token of peace.”

(c. 1547 - c.1618)

Powhatan Confederacy

First Leader in Contact With the Jamestown Settlers

Best known as Pocahontas’ father, Chief Powhatan (a.k.a. Wahunsenacawh) was the supreme Indigenous leader in the Chesapeake Bay region of Virginia, who built a confederacy of dozens of tribes—through force, marriage and by "adoption." In the early 1600s, Chief Powhatan adopted Englishman John Smith as a wereowance, or leader, of what would eventually become Jamestown Colony. But when relations with the English settlers soured, he ordered his warriors to attack James Fort in 1609, initiating the first Anglo-Powhatan war. That lasted until the marriage of his daughter Pocahontas to English colonist John Rolfe. After she died in 1617, Powhatan ceded his rule to his brothers, Opechancanough and Itoyatan.

A code talker was a person employed by the military during wartime to use a little-known language as a means of secret communication. The term is most often used for United States service members during the World Wars who used their knowledge of Native American languages as a basis to transmit coded messages. In particular, there were approximately 400 to 500 Native Americans in the United States Marine Corps whose primary job was to transmit secret tactical messages. Code talkers transmitted messages over military telephone or radio communications nets using formally or informally developed codes built upon their indigenous languages. The code talkers improved the speed of encryption and decryption of communications in front line operations during World War II and are credited with some decisive victories. Their code was never broken. There were two code types used during World War II. Type one codes were formally developed based on the languages of the Comanche, Hopi, Meskwaki, and Navajo peoples. They used words from their languages for each letter of the English alphabet. Messages could be encoded and decoded by using a simple substitution cipher where the ciphertext was the Native language word. Type two code was informal and directly translated from English into the Indigenous language. Code talkers used short, descriptive phrases if there was no corresponding word in the Indigenous language for the military word. For example, the Navajo did not have a word for submarine, so they translated it as iron fish. The term Code Talker was originally coined by the United States Marine Corps and used to identify individuals who completed the special training required to qualify as Code Talkers. Their service records indicated "642 – Code Talker" as a duty assignment. Today, the term Code Talker is still strongly associated with the bilingual Navajo speakers trained in the Navajo Code during World War II by the US Marine Corps to serve in all six divisions of the Corps and the Marine Raiders of the Pacific theater. However, the use of Native American communicators pre-dates WWII. Early pioneers of Native American-based communications used by the US Military include the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Lakota peoples during World War I. Today the term Code Talker includes military personnel from all Native American communities who have contributed their language skills in service to the United States. Other Native American communicators—now referred to as code talkers—were deployed by the United States Army during World War II, including Lakota, Meskwaki, Mohawk, Comanche, Tlingit, Hopi, Cree, and Crow soldiers; they served in the Pacific, North African, and European theaters.

Crazy Horse was born on the Republican River about 1845. He was killed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in 1877, so that he lived barely thirty-three years. He was an uncommonly handsome man. While not the equal of Gall in magnificence and imposing stature, he was physically perfect, an Apollo in symmetry. Furthermore he was a true type of Indian refinement and grace. He was modest and courteous as Chief Joseph; the difference is that he was a born warrior, while Joseph was not. However, he was a gentle warrior, a true brave, who stood for the highest ideal of the Sioux [Lakota.] Notwithstanding all that biased historians have said of him, it is only fair to judge a man by the estimate of his own people rather than that of his enemies. The boyhood of Crazy Horse was passed in the days when the western Sioux saw a white man but seldom, and then it was usually a trader or a soldier. He was carefully brought up according to the tribal customs. At that period the Sioux prided themselves on the training and development of their sons and daughters, and not a step in that development was overlooked as an excuse to bring the child before the public by giving a feast in its honor. At such times the parents often gave so generously to the needy that they almost impoverished themselves, thus setting an example to the child of self-denial for the general good. His first step alone, the first word spoken, first game killed, the attainment of manhood or womanhood, each was the occasion of a feast and dance in his honor, at which the poor always benefited to the full extent of the parents’ ability. Big-heartedness, generosity, courage, and self-denial are the qualifications of a public servant, and the average Indian was keen to follow this ideal. As everyone knows, these characteristic traits become a weakness when he enters a life founded upon commerce and gain. Under such conditions the life of Crazy Horse began. His mother, like other mothers, tender and watchful of her boy, would never once place an obstacle in the way of his father’s severe physical training. They laid the spiritual and patriotic foundations of his education in such a way that he early became conscious of the demands of public service.

Comments

Post a Comment