Mythologies of the Chiripá Tribe

The Chiripá are a Guaraní indigenous people who live mainly in Paraguay in the area bounded by the Paraná River and the Acaray and Jejuí Rivers, while in Brazil they coexist with other Guarani groups in villages in the states of Mato Grosso do Sul (where they are simply called Guarani), Paraná and São Paulo. The term ñandéva is used in Paraguay to refer to the tapietes. In Argentina they are found in small groups living among the Mbyas in the province of Misiones. They are highly acculturated but maintain their dialects and religious traditions. In Paraguay, around 2002, there were about 6918 people of this ethnic group (1900 speakers of the language). According to the results of the III National Population and Housing Census for Indigenous Peoples of 2012, there were 17,697 Avá Guaranis, 9,448 in whom live in the Canindeyú Department, 5,061 in the Alto Paraná Department, 1,524 in the San Pedro Department, 946 in the Caaguazú Department, 379 in Asunción and the Central Department, and 142 in the Concepción Department. In Argentina, The Avá Guaraní live in small groups among the Mbyá in Misiones Province. In the village of Fortín Mbororé, near Puerto Iguazú, there is an important group that lives with a Mbyá majority. They are highly adapted but retain their dialects and religious traditions. The 2010 Argentina census revealed the existence of 422 people who identified themselves as Avá Guaraní in the province of Misiones and 104 in the province of Corrientes, but it is impossible to distinguish how many of them may belong to the Chiriguano group. There are still about 4,900 Avá Chiripá (also Avakatueté or Avá katú eté), Tsiripá or Apytaré (also Ñandéva) in Brazil. The Ñandéva language is spoken in the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso do Sul and Paraná, on the Iguatemi River and its tributaries, equally near the confluence of the Paraná and Iguatemi Rivers. Also called the Avá-Guaranies of Paraguay, Avakatuetés, Avá Katú etés, Avá Chiripás, Tsiripá and/or Apytaré self-proclaimed Ñandéva in Brazil.

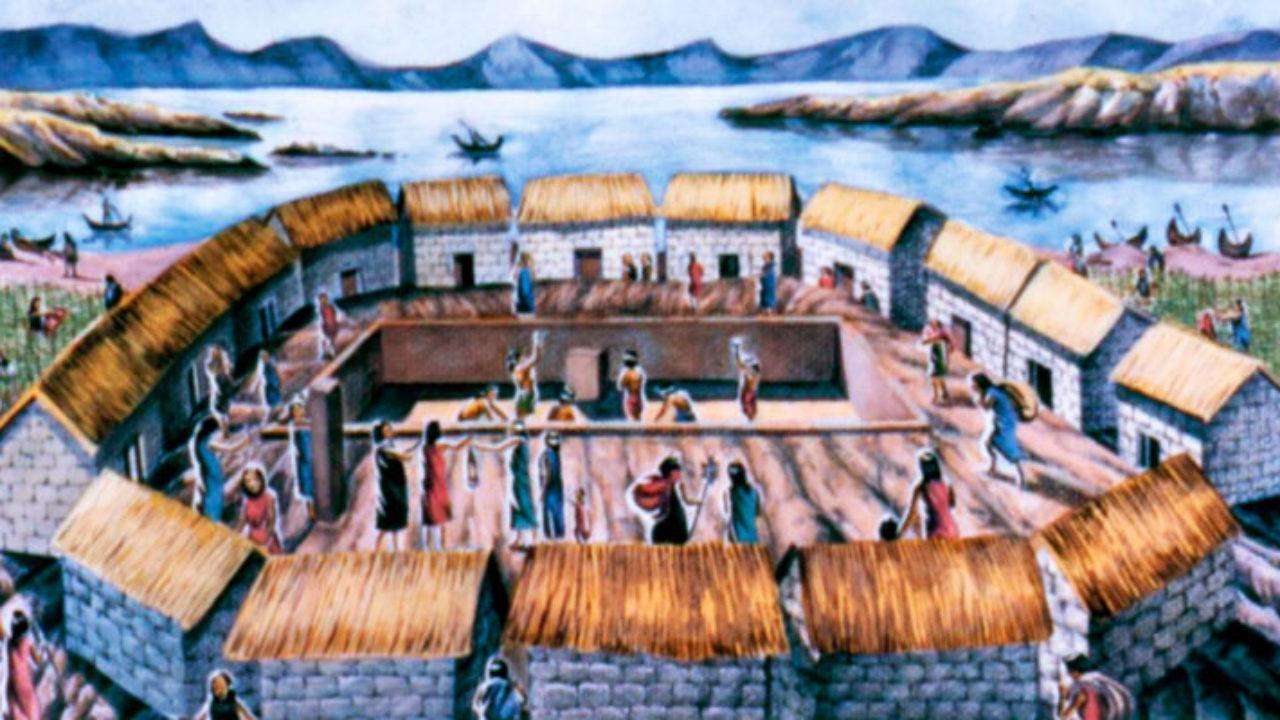

The Chiripa culture existed between the Initial Period/Early Horizon, from 1400 to 100 BCE along the southern shore of Lake Titicaca in Bolivia. The site of Chiripa consists of a large mound platform that dominates the settlement. On the platform is a rectangular sunken plaza (22 m × 23.5 m (72 ft × 77 ft) and 517 m2 (5,560 sq ft)) with a carved stone in the center of the plaza. Rituals occurred in specially prepared public places like the plaza, suggesting the importance of rituals in the creation and maintenance of legitimacy and power. There are fourteen upper houses with thatched roofs and double walls of cobble and adobe, arranged in a trapezoid surrounding the sunken plaza. These were first identified by Bennet (1936). Each had decorative wall paintings, prepared yellow clay floors and between building wall bins, believed to be for ceremonial storage. Access to the plaza and upper houses was limited to two openings, each on the North and South side of complex. Access to individual upper houses was a single stone door. Access to wall bins was by single ornate window. Bennet (1936) excavated burials in the floors of one of the upper houses. Most of the stone-marked burials were children or infants. Adult burials were not usually marked. Gold, copper, shell, and lapis goods were found in many of the stone-marked infant/child graves. While these goods were only found in the one stone-marked adult grave. Adult skeletal remains were often found in bundles in parts of the site above ground. Variability in grave goods and structure of burials may suggest different statuses in society.

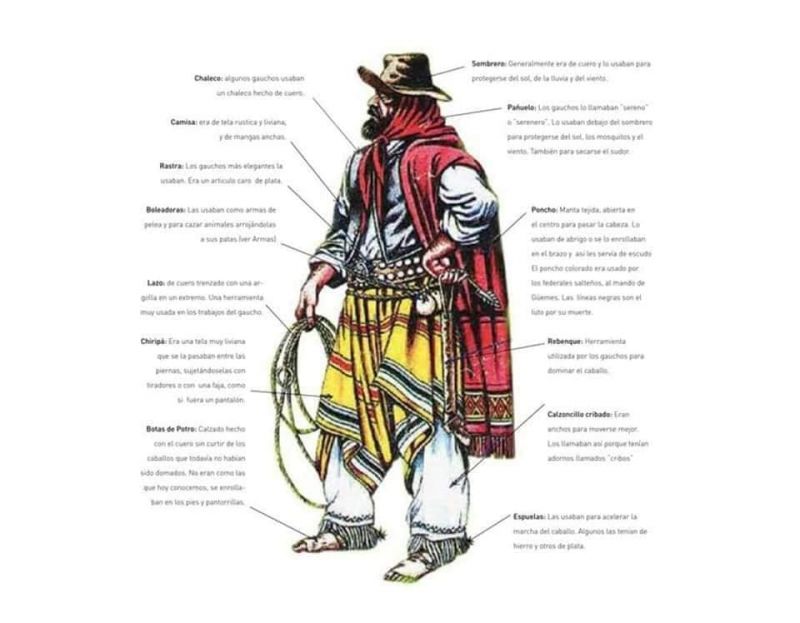

Gauchos of the Río de la Plata adopted many elements of pre-Columbian culture, including clothing. The original peoples of South America developed the chiripá (a word of probable Quechua origin), a rectangular cloth worn like a diaper. After passing the cloth between his legs, a man secured it around his waist with a stout belt (tirador). The seamless garment provided great comfort while riding. Underneath the chiripá, gauchos sometimes wore white, lace-fringed leggings called calzoncillos blancos. During the late nineteenth century, the traditional chiripá gave way to imported bombachas, bloused (usually black) pants taken in at the ankle.

The Chiripa or Nhandeva are one of the tribes of the Guarani nation of South America, and also the name of their dialect of the indigenous Guarani language. The Chiripa language is different enough from other forms of Guarani that many linguists consider it a distinct language. Chiripa is spoken by about 15,000 people in Paraguay, Brazil, Bolivia and Argentina. The name "Chiripa" refers to the style of long loincloth traditionally worn by this band. "Nhandeva" means "our community." "Ava," which means simply "men," is commonly used by the Chiripa to refer to themselves and "Ava-Guarani" for their language, but this has caused a certain amount of confusion since the word ava is the same in nearly all Guarani languages, so many Guarani people from different communities call themselves Ava as well. Chiripa subgroups include the Apapocuva and the Tapiete. Alternate spellings of these names include Chiripá, Tsiripá, Txiripá, Txiripa, Xiripa; Nandeva, Ñandeva; Tapieté; Avá, Abá, Aba, Awá, Awa, Áwa, Avá-Guarani, and Avaguaraní.

The site of Chiripa is located in Bolivia on the southern shore of Lake Titicaca. A series of structures revealed by excavation there have long been interpreted as ordinary houses of a residential village belonging to a relatively localized culture named Chiripa after the site. Using available published data as well as unpublished evidence, I have reinterpreted this unusual Late Chiripa architectural complex (ca. 800100 B.C.), with its structures surrounding a sunken court, as a temple-storage complex. In this article I examine how it served as a direct model for the monumental temple complexes belonging to the later Pucara culture (ca. 100 B.C.) that are found in Peru at Pucara in the northern Titicaca Basin. The occupants of the high-prestige temple/storage complexes at Chiripa and Pucara may have been involved in the administration of ritual and worship, and even of production, distribution, and consumption, perhaps regulated by periodic ceremonies associated with the temples. Chiripa was part of the widespread Yaya-Mama Religious Tradition, defined here for the first time, that appears to have unified populations in the Lake Titicaca Basin. This tradition directly contributed to Pucara, and in many ways persisted into later, more powerful Tiahuanaco, Huari, and perhaps even Inca societies (see map and chronology, pp. 2-3). Beginning at least by Late Chiripa times, the Yaya-Mama Religious Tradition, named after the style of associated stone sculpture, was characterized by: (1) temple-storage centers such as at Chiripa, (2) Yaya-Mama style stone sculpture having supernatural images, associated with the temples, (3) ritual paraphernalia including ceramic trumpets and ceremonial burners, and (4) a supernatural iconography including heads having rayed appendages and a vertically divided eye. Tialmanaco and the local societies that preceded it were set in the altiplano, a high, virtually -treeless plateau that surrounds Lake Titicaca at over 3800 m. above sea level. This region provides both limitations and advantages in terms of subsistence (see Erickson, this issue). The most salient limitation of the cold and altitude was on agriculture, so that crops included only native grains, like quinoa; and tubers, such as the potato. The open grasslands, however, were ideal for the hunting of wild guanaco, vicunas, and deer, and for the herding of domesticated llama and alpaca. In addition, the lake provided abundant resources like fish, fowl, and reeds used for such things as rafts for transport, roof thatching, and food.

Comments

Post a Comment